How to define your inner “Healthy Adult” (with help from Stoicism)

If we are to live our values, we need clarity on what values-based living truly looks like.

“Know, first, who you are, and then adorn yourself accordingly.”

-Epictetus, Enchiridion

Part of what makes Stoicism so relatable is that it provides clear examples of what virtuous living entails. As a Clinical Psychologist, this is refreshing.

My field – Clinical Psychology – does a great job of identifying unwanted modes of thinking and behaving. We’re good at describing what’s not working, but we’ve done a less stellar job of identifying what works – that is, what leads to flourishing, well-being, and equanimity.

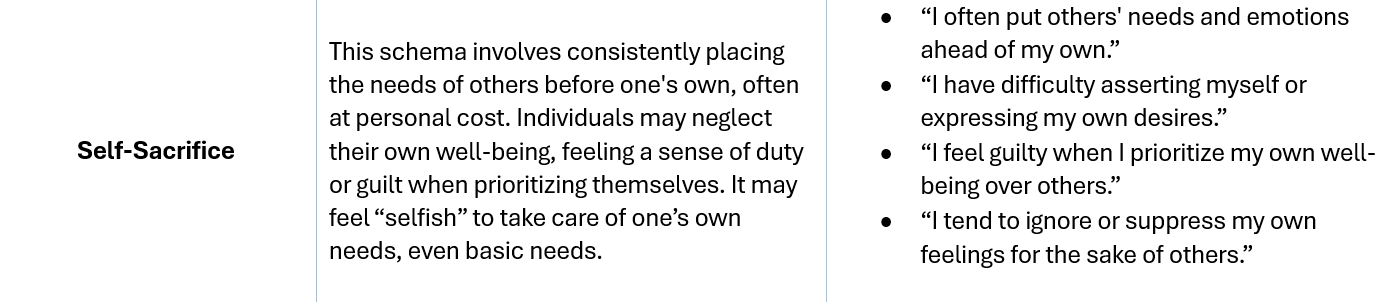

I’m a practitioner of Schema Therapy, an extension of classic CBT. Schema Therapy focuses on a set of 18 “maladaptive” core beliefs (or, schemas) that capture counter-productive patterns of thinking and acting (see this article for a more detailed intro to the concept of schemas).

The over-arching goal of Schema Therapy is to stop living a schema-driven life, and instead live a life directed by your internal “Healthy Adult.” A problem I encounter as a Schema Therapist is that the Healthy Adult mode is not concretely defined.1

So, in a quest to identify not only what doesn’t work, but also what does, I often find myself reaching into domains outside of Schema Therapy, including Stoicism2, Buddhism, and Positive Psychology.

To be honest, I find the term Healthy Adult to be a bit pejorative and unrelatable. I prefer to use terminology that places more emphasis on self-compassion and the pursuit of one’s values, such as your Values-Based Self. Nonetheless, I agree with the intent behind the notion of developing your own inner Healthy Adult.

Beyond introducing you to Schema Therapy, I want to discuss the field’s efforts to define its Healthy Adult mode. Given that Stoicism upholds clear virtues and the image of the Sophos (or Sage) as its aspirational figure, I suggest specific concepts that Schema Therapy could borrow to extend clarity on what exactly Healthy Adult living entails.

A brief note of thanks - in developing this article, I was fortunate to be able to consult with author Donald J. Roberston. He’s one of the preeminent contemporary writers examining the link between Psychotherapy and Stoicism.

Which Schemas Do I “Have?”: A Condensed Guide to Schema Therapy

In our early years, little humans need to find ways to get the support and affection of the adults around them.

Did you have a parent who always asked you to “do just a little better” or “just a little more?” If you did, it made sense that you ended up putting pressure on yourself to succeed, often delaying your own gratification. You might have then been rewarded for “being the good kid” at home or at school, which reinforced a pattern of having high standards for your achievement. So, you developed the strategy of denying your own needs to meet these standards.

If this example resonates with you, you might “have” the Unrelenting Standards schema.

What about always being told to “always let other kids go first” or “always be polite and don’t ask for anything that isn’t offered to you”? If your parents consistently gave you messages like this, you learned that the approval of others is critical and it’s contingent on not expressing your needs.3

This could have caused the development of an Approval Seeking or Self-Sacrifice schema.

From a Clinical Psychology lens, schemas are the rules and patterns we learn for interacting with the world:

A negative schema is made up of a specific pattern of thoughts, emotions, beliefs, bodily sensations, and neurobiological reactions, and is developed when a core emotional need such as that for connection and acceptance, autonomy, reasonable limits, or realistic expectations is not adequately met during childhood (Lockwood & Perris, 2012; Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003). For example, the Emotional Deprivation Schema arises when the core emotional need for connection and acceptance is not met from a stable and predictable primary caregiver. Other secondary factors that also contribute to the development of schemas include culture, birth order, the quality of the parent’s marriage, and a child’s temperament (Louis & Louis, 2015; Young et al., 2003).4

Schemas develop because on some level they make sense - they work in terms of getting certain needs met, especially in the environment that you grew up in.

Your schemas become the lenses through which you see yourself, the world, and other people. Although we all have both helpful and unhelpful schemas, it’s the unhelpful ones that motivate clients to start therapy. Enhanced awareness of your schemas and how they manifest is empowering and helps you to ensure that you’re not reflexively perpetuating unwanted patterns in your life.

Schema Therapy posits 18 core maladaptive schemas. In the table below, I’ve included examples of some that I see most frequently in clinical practice.

The Alternative – Positive Schemas

It’s easy to “follow” our maladaptive schemas. After all, they represent the rules we learned growing up. But, they generally lead to unsustainable work, relationship, or self-care habits. Left unchecked, your schemas can colour virtually any (or, all) facets of your life.

If we agree that we don’t want to reflexively perpetuate our maladaptive schemas, what’s the alternative?

In Schema Therapy, that’s where the Healthy Adult Mode comes in:

“The healthy adult mode is the adaptive self-regulating aspect of a person. Naturally, in this mode, the person integrates reasonable thoughts and self-insight, leading to functional problem solving. This mode nurtures, validates, and affirms the vulnerable child mode and regulates the angry and impulsive child modes.5 In healthy adult mode, the person reappraises the beliefs of the inner critic modes and chooses her own functional values…She performs appropriate behaviors such as working, parenting, taking responsibility, and committing. She pursues pleasurable adult activities, such as “good” sex; intellectual, aesthetic, and cultural interests; health maintenance; and athletic activities. There’s a good balance of her own and others’ needs. The healthy adult mode is the “therapist inside” that is strengthened in therapy…It is the job of the healthy adult to reappraise the old beliefs and balance the needs for attachment and assertiveness, resulting in functional coping behavior….[The Healthy Adult Mode is] an invisible regulating mental function that induces functional [values-based] coping behavior.”6

Schema Therapy literature often includes qualitative descriptions of Healthy Adult functioning, like the one above. I argue, however, that descriptions of what the Healthy Adult looks like are helpful, but they don’t go far enough.

Recognizing this issue, Louis et al. (2018), conducted a detailed set of large studies for the purpose of running factor analyses on statements associated with positive schemas. Given that Schema Therapy posits 18 common maladaptive schemas, they wanted to see if they could rigorously substantiate a corresponding set of positive schemas. Their approach builds on some of the earliest Positive Psychology efforts aimed at identifying core “character strengths.”7

It may sound like common sense to try to identify corresponding positive schemas. In many ways, it is. However, keep in mind that the history of modern Clinical Psychology is heavily biased towards a focus on what’s not working. It’s only been in the past couple decades that the field has, in earnest, turned its attention towards well-being.

Ultimately, the Louis et al. study identified 14 constructs representing 14 positive schemas.

If the Healthy Adult Mode is an aspirational image of what we want to strive towards in the pursuit of functionality, balance, and a life, we can see the 14 positive schemas as the specific traits and beliefs that we want to manifest. Taken together, they provide an image of a securely attached, confident, competent, and generally reasonable human being. As we can imagine, such an individual likely experiences relatively high levels of general equanimity and internal emotional well-being.

Let me paint a picture of who this adaptive person is, providing a brief summary of each of the 14 positive schemas. But, before I do, remember that the 14 positive schemas represent an aspirational mode of being. We want to “move towards” the Healthy Adult Mode - the constructs represent a direction for your life, not a destination. For God’s sake do not expect yourself to possess all of these traits. You can’t force yourself to always be in Healthy Adult Mode and one never reaches a day where they “achieve” Healthy Adult “status.” Here are the 14 positive schemas identified by Louis et al.:

1. Emotional Fulfillment Schema (antidote to the Emotional Deprivation and Defectiveness Schemas): Letting yourself get close to – and develop bonds with – others. Acknowledging that certain people can understand you emotionally and meet your emotional needs (and that you don’t have to be perfect for that to happen).

2. Success Schema (anti-dote to the Failure Schema): Seeing yourself as generally competent, or able and willing to learn if you don’t already have a certain skill or set of knowledge.

3. Empathic Consideration Schema (anti-dote to the Entitlement Schema): Being able to accept no for an answer (within reason) and not having to “run the show all the time.” Being flexible with your expectations of others and appropriately considering their needs and rights.

4. Basic Safety and Optimism Schema (anti-dote to the Pessimism and Vulnerability to Harm Schemas): Recognizing the limits of worry and not dwelling unnecessarily on concerns about safety, health, finances or other vulnerabilities. Having a healthy acceptance of risk and uncertainty – accepting that nothing is perfect, and nothing is perfectly risk-free. Pulling back from catastrophizing.

5. Emotional Openness and Spontaneity (anti-dote to the Emotional Inhibition Schema): Allowing yourself to show emotions, including unwanted emotions and vulnerabilities to others, as appropriate. Also related to positive emotions and letting yourself be warm and spontaneous.

6. Self-Compassion Schema (anti-dote to the Punitiveness Schema): Forgiving yourself when making a mistake and knowing how to acknowledge it without punishment/self-flagellation. Giving yourself the benefit of the doubt. This doesn’t mean self-pity or being unaccountable.

7. Healthy Boundaries Schema (anti-dote to the Enmeshment Schema): Having healthy boundaries and a developed sense of yourself, separate from others and others’ needs/values. Being an independent person not excessively enmeshed with the needs/desires of others.

8. Social Belonging Schema (anti-dote to the Social Isolation Schema): Feeling a general sense of “belonging” socially. Allowing yourself to be and feel included in groups and to connect socially with others.

9. Healthy Self-Control / Self-Discipline Schema (anti-dote to the Insufficient Self-Control Schema): Having reasonable discipline and self-control, particularly with regards to routine or boring tasks. Sticking to resolutions and persevering towards goals, within reason (not at the expense of the Self-Compassion and Realistic Expectations/Standards Schema).

10. Realistic Expectations/Standards Schema (anti-dote to the Unrelenting Standards Schema): Having realistic expectations. Generally hoping to achieve your goals but also acknowledging that you don’t have to be perfect and that “good enough is good enough.”

11. Self-Directedness Schema (anti-dote to the Subjugation8 and Approval Seeking Schemas): Placing values-based self-direction over getting others’ approval or praise. Not being primarily driven by others’ approval or “fitting in.”

12. Healthy Self-Interest / Self-Care Schema (anti-dote to the self-sacrifice Schema): Being able to exercise “healthy selfishness” in terms of being mindful of your own interests and self-care. Able to work hard but also leave time for leisure.

13. Stable Attachment Schema (anti-dote to the Abandonment and Mistrust Schemas): Allowing yourself to feel secure in relationships; not needing to cling to others. Generally assuming that people will not leave, abandon, or betray you.

14. Healthy Self-Reliance / Competence Schema (anti-dote to the Dependence Schema): Notwithstanding the need for social connection, being able to function independently and in a self-reliant manner. Having confidence in yourself to generally solve problems as required in day-to-day contexts, or at least the willingness to try.

The utility of the 14 positive schemas is in pointing us towards healthy anchors for how we relate to ourselves, others, and the world around us. They are the anti-dotes to our built-in evolutionary and learned thinking traps and vulnerabilities. They are skills to be practiced and honed.

Do we have a clear enough picture of the Healthy Adult?

Now that I’ve provided qualitative information about what the Healthy Adult looks like and outlined the 14 specific, quantitatively derived positive schemas, do you feel like you have enough information to go out and live your Healthy Adult life?

My guess is that your response is something approximating, “not quite.”

I’m being somewhat tongue-in-cheek – obviously changing problematic schemas and developing new, healthier schemas takes a lot of work. Manifesting your own values-based, compassionate healthy adult takes trial and error, often done working with a qualified therapist.

My point though, is that Schema Therapy could go further in painting a clear picture of what Healthy Adult living really looks like. Part of this clarity may come from comparing its constructs and practices to those of ancient traditions, like Stoicism.

Enter Stoicism

Like proponents of Schema Therapy, the Stoics also upheld an aspirational ideal to strive towards.

Perhaps the Stoic equivalent of Schema Therapy’s Healthy Adult Mode and its associated positive schemas, is the Sophos, or sage – one who has attained wisdom. A Sophos is one who has mastered the Stoic virtues.

Attaining wisdom in the Stoic sense requires consistent reflection on what is often referred to as the Stoic Fork.

Like a fork in the road, the Stoic Fork is the idea that there are:

things within our control (e.g., certain choices and actions)

things outside our control (e.g., external events and others' opinions)

Stoic authors like Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus advised focusing staunchly on what you control and accepting what you don’t. This is liberating. By extension, Stoicism calls on us to question over-attachment to externals – this encompasses being too preoccupied with the opinions of others and too averse to discomfort.

These points of advice are key ingredients for an equanimous life.

If there's something in Schema Therapy approximating the Stoic Fork, it’s that your schemas try to have you "manipulate" or "control" your environment in order to get your needs met and ultimately be accepted by (or function in) the world.

This often manifests in having harsh standards, trying to get others’ approval, or pushing your own needs under the rug. Sometimes your schemas also lead to fear and avoidance, giving you the message that you’re fragile or defective and that you shouldn’t go out and live your values.

But, if we look at the descriptions we have of the Healthy Adult, they don’t explicitly include emphasis on identifying the line between what you control and what you don’t.

To me, any fulsome image of the Healthy Adult needs to include emphasis on something approximating the Stoic Fork – you don’t control everything and you can’t control everything. You need to give yourself permission to focus solely on what is within your control.

But, what is within our control?

Well, we always have control of moving towards our values.

No matter the situation, we can try to align our behaviours with our values.

This requires knowing our values.

Qualitative descriptions of the Healthy Adult certainly reference identifying and living one’s values (often borrowing from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) but the absolute importance of values identification could be stated much more explicitly in the Schema Therapy literature. You’ll also notice that the list of 14 positive schemas makes no reference to values or values identification.

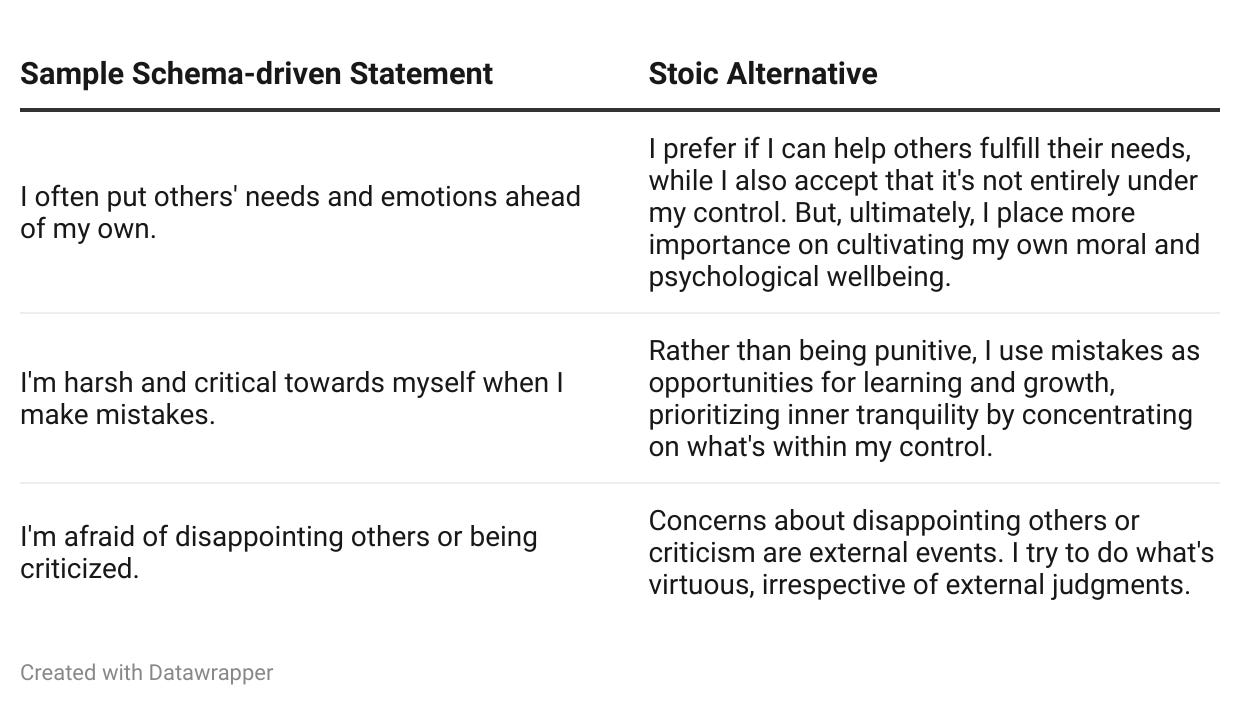

Herein lies another area where Schema Therapy could borrow from Stoicism. Stoicism emphasizes the practice of questioning and clarifying values. This practice is integral to the ancient Socratic method and Stoic philosophy, as is the effort to live more consistently in accord with them, from moment to moment, throughout each day.

Stoicism is explicit in outlining key values, like wisdom (making judgments and choices in accordance with reason), courage (facing challenges and adversity with resilience and strength, even when you’re scared), justice (treating others with fairness, equity, and respect), and temperance (exercising moderation and self-control in desires and impulses).

Below are examples of Schema-driven statements and, alternatively, how a Stoic might see things:

Final Word

Schema Therapy represents an incredibly helpful framework for understanding human struggle. There is great heuristic value in being able to label and identify the patterns that emanate from specific schemas.

Schema Therapy could benefit from expansion and clarification of its aspirational Healthy Adult figure. Efforts are underway in this regard. These efforts, I believe, could help extend the reach of Schema Therapy by providing greater clarity on what Healthy Adult functioning really looks like in practice.

A high-level comparison to key tenants of Stoicism reveals at least two major elements of Stoicism that appear important for Schema Therapy to “borrow” in expanding and clarifying its concept of the Healthy Adult:

The Stoic Fork – emphasis on the distinction between what one controls and what one doesn’t.

Values Clarification – emphasis on knowing one’s values and on recognizing that what one does control is moving towards one’s values. I feel that Schema Therapy could also be more explicit in outlining specific values, similar to how some proponents of Positive Psychology uphold specific character strengths.

Undoubtedly, there are other Stoic principles – namely, characteristics of the Sage – that could be borrowed by Schema Therapy to provide a clearer picture of its Healthy Adult figure. Chief among these may be the Stoic concept of mindfulness (or, prosoche) and, related, Stoic treatments of concepts such as transience and impermanence.

Certainly, there is a tradition of contemporary therapies such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy adapting concepts from “ancient” philosophies (most explicitly Buddhism). For whatever reason, Schema Therapy literature has rarely been explicit about this type of borrowing and integration.

Going forward, Schema Therapy could benefit from borrowing examples of healthy behaviour from Stoicism, a philosophy rich with first- and second-person examples of adaptive, values-based cognitive and behavioural practices.

Such an exercise need-not be provincial, and I believe that further steps in clarifying the characteristics of the Healthy Adult should involve cross-referencing related modalities including Buddhism and Positive Psychology.

To that end, please let me know of concepts from other traditions and modalities - including Stoicism - you feel could be relevant to creating a clearer image of Schema Therapy’s Healthy Adult. Please comment below or send your thoughts directly.

Identifying an aspirational image of your values-based self can be deeply personal - don’t be shy about identifying concepts and strategies that resonate uniquely with you!

This has been echoed by Salicru, who has proposed an “octopus” metaphor for the Healthy Adult: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=125740

There’s at least some similarity between Stoicism and Schema Therapy. Both approaches emphasize self-monitoring of problematic patterns and the development of specific, healthier patterns. Pioneering texts associated with the development of what is now known as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, made specific reference to Stoicism as an influence on their thinking in the development of cognitive and behavioural interventions. For more, see: Robertson, D., & Codd, R. T. (2019). Stoic philosophy as a cognitive-behavioral therapy. The Behavior Therapist, 42, 42-50.

Of course, some parents are downright abusive or neglectful and, of course, this type of parenting also contributes to the development of maladaptive schemas.

Quote from Louis, J. P., Wood, A. M., Lockwood, G., Ho, M. H. R., & Ferguson, E. (2018). Positive clinical psychology and Schema Therapy (ST): The development of the Young Positive Schema Questionnaire (YPSQ) to complement the Young Schema Questionnaire 3 Short Form (YSQ-S3). Psychological Assessment, 30, 1199.

The Schema Therapy models posits a number of maladaptive schema-driven modes such as Vulnerable Child, Inner Critic, Detached Protector, Compliant Surrenderer, and Detached Self-Soother. The model also emphasizes “coping styles” such as surrender, avoid, and over-compensate. A full discussion of the model, by necessity, requires discussion of these modes that is outside the scope of this article. For a condensed overview of the model though the lens of the self-compassionate healthy adult see: https://drjeffperron.substack.com/p/a-detailed-guide-to-self-compassion

Roediger, E., Stevens, B. A., & Brockman, R. (2018). Contextual schema therapy: An integrative approach to personality disorders, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal functioning. New Harbinger Publications.

E.g., see Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press and Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.”

Technically Subjugation correlated highly with Success, but this appears to have less face validity than how it is categorized here.

Great article, thank you! It's amazing how ancient Stoic philosophy still has practical applications in the modern world of psychology.

Broadly useful and helpful language, content, and thinking tools, and for applying the Stoical “view from above”!